What follows is the first sermon I ever wrote and preached — at Kingston Road United Church in east Toronto on July 18, 2004. I am publishing it here because it is now 35 years since the Sandinista triumph on July 19, 1979, and because my sermon for this coming Sunday will refer to this one — Ian, Edmonton, July 24, 2014.

Good morning! I am very pleased to speak to you today about an event that means a lot to me, the 25th anniversary of the Nicaraguan Revolution. I want to thank Rev. Rivkah Unland and the Worship Committee for allowing me to use this service to celebrate this anniversary.

My remarks are a chance for me to connect one of my old passions — for political activism — with my newfound passion for church. So, I am grateful for that as well.

I asked Ruth Pentinga and Rob C. to perform Sting’s song Fragile this morning since it is a song inspired by Nicaragua.

Sting wrote Fragile in 1987 when he learned about the murder of three men who were helping to build a hydro dam in Nicaragua. They were killed by the contras, or the counter-revolutionaries. As some of you will remember, and as I will explain more in a few minutes, the contras were a U.S. organized and funded military group that wrecked havoc on Nicaragua in the 1980s. They killed thousands of people and caused economic devastation through sabotage.

Given the violence of the contras, there was nothing unusual in these three deaths in 1987, except that one of the murdered men, a 23-year old engineering student named Ben Linder, was not a Nicaraguan – he was an American humanitarian aid worker.

Because Ben Linder was an American, killed by an American-backed military group, his death became a big story. It put extra pressure on U.S. President Ronald Reagan to reverse his policy of trying to overturn the Nicaraguan Revolution. Reagan was already dealing with the Iran-Contra scandal, which had been uncovered in late 1986.

Some of you will also remember this scandal – how the Reagan government secretly and illegally sold arms to Iran and diverted the proceeds to the contras fighting against Nicaragua. Reagan had resorted to the Iran/Contra dealings because the U.S. Congress had forbidden further CIA funding of the contras. Oliver North was involved. It was an embarrassing mess. So for Reagan, the death of Ben Linder came at an awkward time.

In his song about the death of Ben Linder and his colleagues, Sting wrote: “Nothing comes from violence and nothing ever could.” However, Sting’s refrain – about how fragile we are – reminds us of why violence works. We live in fragile bodies. We are mortal. We can be made to feel pain, and we can be terrorized by the threat of pain or death. It is precisely this fragility that makes violence so damnably effective and so damnably common.

Nicaragua’s story has a lot to say about how to confront violence. That is one of the reasons I asked to speak this morning. Unfortunately, its story also shows how difficult it is to sustain a realm of peace and justice in a violent world. So, for me the July 19th anniversary is both a joyous and a sombre occasion.

. . . . .

25 years ago tomorrow on July 19th 1979, the people of the small country of Nicaragua accomplished a kind of miracle – they overthrew an American-backed military dictatorship.

Nicaragua is in Central America — the narrow land bridge that connects North and South America – and it has about four million people.

Nicaragua has always been a very poor and unimportant place. Since its independence from Spain in the 1820s, Nicaragua has been politically and militarily dominated by the United States. The U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua between 1912 and 1933. When they left, the Marines installed the first of three members of the Somoza family as the president/dictator of the country. After that, Nicaragua languished in obscurity and misery until the 1970s.

. . . . .

In 1979, when the Nicaraguan revolution occurred, I was a student activist and socialist at York University. While I was aware of the revolution, I must admit that at first, I didn’t pay it much attention. I assumed it would be like dozens of other doomed attempts of oppressed countries in the South to overcome domination and poverty.

But in 1982 and 83, when I was active in the peace movement here in Toronto, I met more and more people who were also active in solidarity with revolutionary Nicaragua. Speaking with these people gave me a new sense of Nicaragua’s importance.

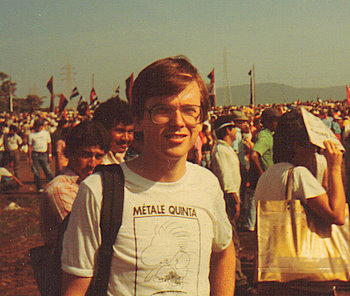

Twenty years ago this week, in 1984, I travelled to Nicaragua along with 17 other people from Canada to witness the fifth anniversary of the 1979 triumph. I loved the two weeks we spent in Nicaragua for many reasons: the friendships I made with the other people on the tour, my first experience of being in a poor country, the many wonderful Nicaraguans we met and talked to, and the things that we learned.

Above is a picture of me in Managua on July 19, 1984

After this trip, I was quite inspired, and I became more involved with solidarity work back here in Toronto. This work involved educational events, protests against U.S. aggression, and humanitarian aid campaigns. Our biggest annual event was a fund-raising dance, always held on the weekend closest to July 19th, in which we conjured up some of the spirit of Nicaragua.

. . . . . .

The Nicaraguan revolution of 1979 came out of a long period of struggle against the dictatorship of the Somoza family. During the years of Somoza family rule any campaign for social reform was met with brutal repression. The jails and torture chambers were filled with dissidents, and the number of people murdered or disappeared by the state was appalling. Despite this repression, social movements to alleviate poverty and for basic human rights were very active and creative.

A huge coalition was slowly formed between poorly armed Sandinista revolutionaries, the popular wing of the Roman Catholic Church, the non-Somoza business sector, and numerous workers’, farmers’, women’s, and student organizations. Through the 1970s, they organized, educated, and resisted. This work culminated in three insurrections in 1978 and 79 in which almost 50,000 ordinary Nicaraguans were murdered by their own government forces. But by July 1979, the Nicaraguan military finally cracked and collapsed; Somoza fled the country; and the revolutionary coalition took power.

This was the triumph of 25 years ago — July 19th, 1979. Although the country was in ruins, Nicaraguans were euphoric that they had expelled their dictator and disarmed and dispersed his military madmen.

In the free space created by the disintegration of the army, the anti-Somoza movement created a radical democracy. It was centered among the militant and organized people – farmers, workers, student groups, and neighbourhood groups.

What did this grass roots democracy accomplish? It abolished capital punishment and outlawed torture. It harnessed the enthusiasm of tens of thousands of young people in a campaign that raised the literacy rate from 50% to 85% in just one year. It distributed land to landless farmers. It oversaw a huge rise in the standard of living through public health campaigns, improved schools, and better nutrition. It encouraged a renaissance of art and culture. And as often happens when dark times finally lift, it led to a huge baby boom.

The Nicaraguan Revolution, unlike others from the English and French revolutions onward, was not anti-clerical. Many of the revolutionary leaders first got involved in politics through Roman Catholic student groups or Catholic neighbourhood base communities.

Many Catholic priests and nuns served in the Nicaraguan revolutionary government, including the Minister of Culture, the head of the Human Rights Commission, and the Nicaraguan Ambassador to the United Nations.

I myself attended my first Roman Catholic mass in Nicaragua 20 years ago.

Unfortunately, the wonderful reforms in Nicaragua did not go unchallenged. The U.S. had lost a client military government in a region that was in turmoil. Other Central American countries were similar to pre-revolutionary Nicaragua — under the thumb of the U.S., ruled by repressive dictators, and facing popular revolt. In particular, El Salvador was on the brink of its own revolution. To prevent this, the death squads there were raining terror down on the head of the Salvadoran people.

Reagan’s administration decided that the inspiring example of Nicaragua could not be allowed to stand. The U.S. government redoubled its military aid to the unspeakable butchers of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, and it rallied and organized the remnants of Nicaragua’s hated National Guard, in exile in Honduras, into the so-called “contras” – the counter-revolutionaries.

The contras main work was economic sabotage and the murder of civic leaders – teachers, nurses, members of farming co-ops, mayors, and so on. During my two weeks in Nicaragua, we attended a mass funeral for victims of the contras and visited the site of a destroyed agricultural depot.

In the 10 years of the contra war, thousands more were killed. The Nicaraguans, already weary of the repression and loss of life of the Somoza years, were soon faced with even more loss and even more fear.

While the economy had boomed in the early years after 1979, by the mid- to late 80’s it crashed. Nicaragua had to pour precious resources into its army to try to defeat the contras. The economic toll of the sabotage escalated. And an embargo by the U.S. sealed the destruction of the economy.

Nicaragua had created a liberal constitution and it conducted national elections in 1984 and 1990. In 84, the main revolutionary party, the Sandinistas, won a resounding victory.

But in 1990, exhausted by the war with the contras, terrorised by the continuing bloodshed, and with its economy once again destroyed, the country voted again. This time the Sandinistas only got 40% of the vote and they lost political power.

Today, after further elections in 1996 and 2001, the Sandinistas remain the leading opposition party. But the electoral defeat for the Sandinistas in 1990 effectively marked the end of the Nicaraguan revolutionary experiment. The U.S. had stomped out Nicaragua’s example, and Nicaragua went back to being an impoverished, miserable, and unimportant country.

. . . . .

Despite this defeat, many achievements of the revolution still stand.

Nicaragua showed that it was possible to overthrow a brutal tyrant like Somoza. It showed that a tiny country could withstand the terrifying power of the U.S. for over a decade. It showed that a radical, grassroots democracy could liberate huge amounts of energy with which to tackle our many social problems.

On the cautionary side, it also showed that the U.S. would not allow such radical democracies to survive.

For Nicaragua to have remained free, its type of democracy had to spread to other countries.

Several times, the revolution in El Salvador, next door to Nicaragua, came close to victory, despite horrifying repression. Together, it and Nicaragua would have had a much greater impact than just Nicaragua on its own.

But the revolution in El Salvador did not succeed, and the one in Nicaragua was largely rolled back. U.S. violence towards Nicaragua and throughout Central America had its bitter effect

. . . . .

So, Nicaragua’s story starts with misery, changes into triumph, and then reverts to misery?

Last week, Rivkah asked me where God was in all of this, and at first I didn’t have an answer since that is not how I usually think. But eventually two things came to my mind. The first is about how my work around Nicaragua was an encounter with the spiritual dimension of political work.

When I went to Nicaragua 20 years ago, I was hoping to experience the spirit of the revolution. I realized that this would not be the wild euphoria of the triumph on July 19th, 1979, but I hoped to catch echoes of that spirit in the celebrations of the triumph five years afterwards.

We did feel some of that in the big rally of 500,000 people that gathered in the capital city to celebrate the fifth anniversary. But I was surprised that in many ways I was more moved by the Catholic mass that we attended later that same day in the beautiful Santa Maria de Los Angeles church in a poor neighbourhood in the city. The service was the peasant mass, created by the great Nicaraguan poet and songwriter Carlos Mejia Godoy. It was led by Father Uriel Molina, one of the priests who, by living in a base community and responding to the needs of its poor, became an early supporter of the revolution.

Until that point, I had thought that the popular Church was useful simply as a debating point to counter Reagan’s claim that the Nicaraguans were godless communists. But being at the mass gave me a different insight. The revolutionary Catholics had achieved something that was missing from the political campaigns that I had been involved in since I was 14 years old. The Nicaraguans had combined political action with an awareness of the importance of spirituality in sustaining their work. They tended to their spirits through prayer and worship and incorporated their spirituality into their politics.

Spiritual needs are always present, I believe, when one becomes involved in the struggle for social justice. From a young age I had tried to be involved in radical politics. I was shocked by the violence and injustice of the world. I was confused about how to find a vocation in a society that seemed so insane. I was looking for ideas and campaigns that could make a positive difference and at the same time could provide me with a sense of purpose, a community, and an outlet for my creativity and passion. But often lacking from the political groups that I joined was any discussion of these deep personal needs and how they could be met in our political work.

The Nicaragua work was different. For one, I found it incredibly exciting and urgent – the creativity of free Nicaragua; the challenge that Central America presented to the dominance of the U.S.; the death and destruction that we opposed; and the fragile democracy, with all its world-changing promise, which we were trying to help.

But beyond that, there was this explicit spiritual dimension, and it struck a chord within me.

This is not to say, however, that mixing politics and spirituality is without problems. The mix can also be poisonous. For example, the Ku Klux Klan represents another model of mixing religion with politics. And Reagan said that God was on his side as he funded the contras and propped up the butchers in El Salvador.

Further, there are many spiritual pitfalls in politics: self-righteous anger, ungrounded idealism, even madness. And being explicitly spiritual doesn’t do away with the hard work of trying to discern what political ideas and actions make the most sense. But when the spiritual dimension of a political movement isn’t even acknowledged, the pitfalls are that much harder to avoid.

I think the popular Church in Nicaragua did a pretty good job of it. It had broken from the Church’s historical legacy of preaching submission to repressive authority. Instead, it used ideas similar to the Realm of God that Rivkah often talks about: a realm of peace and justice, with power in the hands of the poor and oppressed.

The second thing that came to my mind in thinking about Rivkah’s question was a story about a controversy among Nicaraguan Christians in the 80s. It concerns the following slogan: “Sandino ayer, Sandino hoy, Sandino siempre!” Sandino refers to a Nicaraguan general, Augusto Sandino, who led the resistance to the U.S. occupation of his country from 1927 until his assassination in 1934. He inspired the later Nicaraguan revolutionaries, and they gave his name to their movement.

In English, the slogan reads, “Sandino yesterday, Sandino today, Sandino forever!” The religious overtones of this slogan upset some conservative Christians, so they countered it with one of their own: “Cristo ayer, Cristo hoy, Cristo siempre!” “Christ yesterday, today and forever!” The conservatives were trying to wrest traditional symbols of death, suffering, and resurrection back from the popular Church.

Perhaps the conservatives had a point. But I like the religious overtones in Nicaraguan songs, poems, and slogans. I mean, why not see Sandino and the other victims of the struggle as Christ? I’m with theologians who believe in the immanence of the divine – the “in-dwelling Christ” or “Christ within” that Paul writes about in his letters; the idea that in baptism one takes on Christ.

In this sense, incarnation doesn’t refer just to the life of Jesus. It refers to all of us … all incarnations of a divine spark of self-consciousness … all doomed to life, growth, suffering, and death. And some of us, like Sandino, meet our death in the struggle for a better world.

As for resurrection, Nicaraguan poems and songs often referred to Sandino and the other martyrs of their struggle as buried seeds, pregnant with the possibility of new life.

In El Salvador, Archbishop Oscar Romero made the link quite explicit. Romero, who preached that the Salvadoran soldiers should mutiny rather than obey their orders to slaughter unarmed protestors, was himself assassinated by a death squad as he stood in his pulpit in 1980. He had written, “I have often been threatened with death. Nevertheless, as a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me, I shall arise in the Salvadoran people. I say so without meaning to boast, with the greatest humility. I am bound as a pastor by divine command to give my life for those whom I love – and that is all Salvadorans – even those who are going to kill me. From this moment I offer my blood to God for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador.”

Where was God, then, in all of this? For many Central Americans, God was with their suffering and torment — the story of the cross in their own lives. And, God was with their joy in the Nicaraguan triumph of 1979 — the story of the resurrection in their own lives.

. . . . .

To close, I offer two suggestions for what we might do today. The first is to mourn and honour the thousands of people killed in Central America in the 70s and 80s. Their sacrifice, as that word implies, is what makes this anniversary sacred to me.

The second is to give thanks that people are periodically moved to break through structures of violence as the Nicaraguans did in 1979. These rare breakthroughs point the way forward to a world of unity, development, and peace. Cultivating awareness that such breakthroughs do happen and can happen again is one of the best reasons to celebrate anniversaries such as the one in Nicaragua tomorrow.

Tomorrow, in Nicaragua, I imagine that the crowds may once again shout what they often did in the 1980s: Sandino vive in la lucha por la paz! Sandino lives in the struggle for peace!

To them and to you I say, Happy Easter! Happy July 19th!

Dear Ian, do email me at audbrook@telusplanet.net so we can exchange information about the annual Genocide Memorial Service, and you can look it up on Google as well. I recently retired as Unitarian Interfaith Chaplain at the U of Alberta, where I served for 10 years. I am pastoral care chaplain with the Unitarian Church of Edmonton. I have a decades long interest in social justice, and have facilitated the Genocide Memorial Service for eleven years. Regards, Audrey Brooks

Pingback: Four spiritual songs | Sermons from Mill Woods

Pingback: The metaphors of life and love | Sermons from Mill Woods